Named and labelled for its centrepiece blue oak tree, Chêne Bleu is making a mark in the wine industry for its high-altitude Rhône Valley blends. Sir Eric Peacock samples some of the brand’s outstanding varietals while speaking with co-founder Nicole Rolet about how the project is exceeding expectations in the wine world.

This article originally appeared in Luxury Briefing issue 215.

Nicole, how would you describe this amazing business that you have?

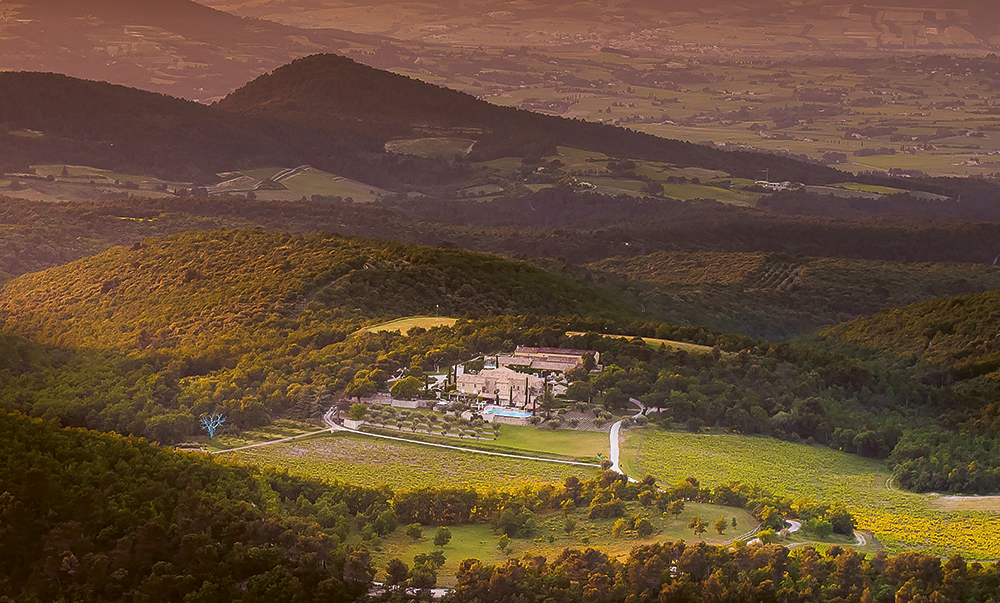

The purpose was to create this little Shangri-La that was at the intersection of all sorts of wonderful things that converged naturally here, plus what we’re bringing to it. My husband [former London Stock Exchange CEO Xavier Rolet] happened upon this ninth-century property. We wanted to restore the site with ancient architecture, wonderful vineyards and create a place where the whole was greater than the sum of the parts. A place where you can seek some sublimation and self-actualisation that’s hard to get in a busy, noisy world. Right from the get-go, it was apparent to us that there was a chance to tick a lot of boxes in hospitality and winemaking, but to go beyond that to create a place where you can really find peace of mind, big ideas and great experiences. I have a background in thought-leadership working in the think-tank world. I always believed beautiful places can be vehicles for a communion of thought and creation of new thought. And wonderful wine also does that – it brings people together. We call it Planet Chêne Bleu! The wine, the hospitality, the wine school, the think-tank, the wine lab – all those things that come together in one place.

When you found this unique place, what was the condition of the vines?

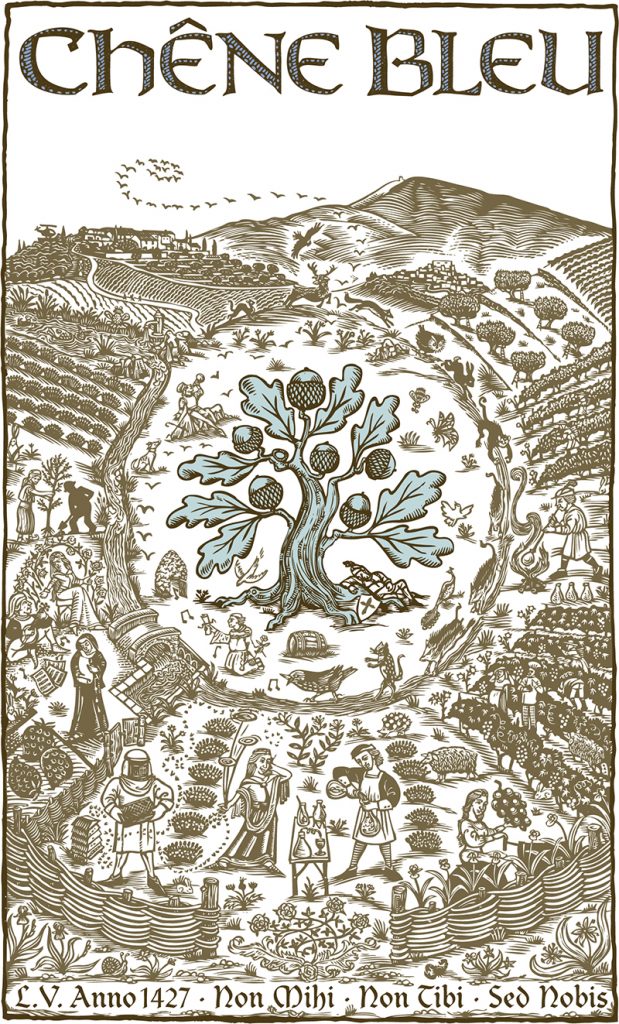

The whole place was a bit like Sleeping Beauty’s castle – it was in complete disrepair. It had no water, no electricity in the house. The vines had been appreciated and valued since the Middle Ages, but there was a mid-20th Century exodus from these high-altitude French properties to the valleys because the yields were so much higher. When my husband came across it, it was in terrible condition. It has this oak tree that we painted blue with copper sulphide like the vines, hence the name Chêne Bleu. Prince Charles had painted the place before we found it, in 1989. He used to spend a lot of time in the region. The style of the wine is this juxtaposition between being very far south and very high up. The tension that comes from these two things is very exciting. I love contradiction, it gives dimension and complexity.

Can you share with us what’s in your range of wines?

Our goal was to show how, even in this tiny remote vineyard, you can find surprising breadth and depth of expression. The whites tend to show, what I would call, the vertical complexity of the vineyard; and the reds show you the whole wingspan of saturation and concentration of flavour. On one end, our Abélard showcases this very muscular Grenache. On the other, Héloïse showcases a very elegant, structured Syrah. In the Rhône, Grenache is the King of the South and Syrah is the Queen of the North and as you move up and down the Rhône Valley, you typically find more of one than the other in the blends. But because we’re so high up, we feel that we have one foot in each territory. It’s about showcasing an ancient land with incredibly complex soils, and we wanted to show what it’s all about. Which is why the Abélard is a Grenache blend with some Syrah, and the Héloïse is a Syrah blend with some Grenache. Together they make this whole. Like they do in the Northern Rhône, we also add a small amount of white wine like Viognier or Roussanne to our Syrah. The idea is to offset the concentration of this very serious Syrah with some of that je ne sais quoi perfume from the white wine.

Now the refurbished property has been brought back to an amazing standard, and you’ve created these wines, what then is on offer for the consumer aside from the wine?

On the hospitality front, our first objective was to allow people to really take in the natural framework. This house was a wonderful testament to the working people of the region who set up an offshoot of the Abbey nearby. We wanted people who visit us to take a moment to think about what it was like to live here with no water or electricity and get a sense of really living off the land. We tried to restore as much of that initial operating process as possible. We have a shepherd, our own lambs, vegetable gardens and a trout basin. As much as possible is sourced from the property and everything is produced organically using biodynamic practices, but we go way beyond that by trying to restore this sense of living independently. It used to take four hours on the back of a donkey to get to the nearest town, but now it takes 12 minutes by car. We wanted to recreate that feeling of escapism and connection to nature. We set up a rental property but transitioned it to be more of

a country retreat where guests can stay in a villa-hotel setting. For the gardens, we worked to have a seamless integration that goes from the house into this very natural environment.

One of the luxuries is to be in a UNESCO biosphere reserve which has 1200 species of butterflies, just to give you one example. The place is teeming with animals and microbiology surviving off this geology. We are right on the edge of a tectonic plate and our vines are growing right on the top of that. As a result, they have a very particular root system which allows them to get watered from subterranean water tables that are sometimes 300 feet below ground. It’s a very extreme environment. The reason it’s important for us is because of the microbiomes. It’s exciting to think that these microorganisms are responsible for taking inorganic matter, processing it and making it into organic matter which is, of course, the source of life. You feel this heartbeat there, of being in a place that is so full of complex geology and microbiology.

You mention how important layering was in terms of the complexity of the wine, and I see that on the labels of your wine.

Absolutely. One of the many challenges that we faced, and still face, was to find a label that sufficiently depicted the many layers of the wine. We built something that was so outside of the box that we didn’t feel we could use traditional iconography. The first thing I wanted was to show the blue oak, which is a symbol of our desire to protect and preserve the history and this environment. I came across the famous paradise triptych from The Garden of Earthly Delights [by Hieronymus Bosch]. If you look at the structure of it, the natural topography of our place is exactly like in this painting. Everything fell into place. I used the golden ratios and then populated it with the metaphors of what I wanted to be represented. The people I’m interested in are those whose idea of luxury is how things are made, what’s gone into them and the care of the craftsmanship and the ideas.

How have you managed to position the wines in the areas that you want them to be, taking into account that it’s a special person that you’re targeting who has that degree of appreciation?

There’s a lot of word of mouth and a lot of early adopters who like it because it’s different. There’s another group of people who want some kind of validation. They might like what you do, but don’t trust their own judgement about the wine itself and they want critics or others to confirm that the product is as good as they like to think it is. It’s important for us to get that validation. We put the wines in a lot of blind tastings, which was extremely important for us because we wanted them to be recognised purely on their oenological merits. That’s been really exciting and gratifying.

I’ve read it’s ‘wine with attitude’?

It’s wine with attitude and altitude – the attitude that we’ve had from the beginning was to stand our ground and aim for top quality. There was a challenge in that I was an American woman coming to the south of France and making wine. We were standing up to a lot of scrutiny and sceptics or people projecting their preconceived notions of who we were and what we were trying to achieve.

And what about the wine school you’ve implemented?

The Extreme Wine Course is the most difficult wine school in the world and its common denominator is the speed with which you learn things, not the level that you’re at when you come in. You can be a complete beginner, intermediate, or very advanced – the goal is to try to take on as much understanding of wine at that next level. There are serious wine courses for the trade, but the intellectual fallacy is that the wines they taste and form your palate on are not the great wines. Yet, if you were to sign up to an art history course, you would like to benchmark your eyes on the best.

In this course, you try to bring the methodologies of the professional wine courses together with the great wines of the world. It’s for wine enthusiasts who are serious about wanting to improve on their knowledge. We make sure that the backbone of the teaching is very intensive, and there are two exams at the end so you benchmark your knowledge. You take the best ideas and best practice from all these other fields and you put them together to create something that you cannot get elsewhere.

You’ve won some impressive accolades, particularly for such a new vineyard, which is quite an achievement.

We had more than 70 medals on our first vintages right away, which was exciting for us. It really helped with proving something to those who were doubting our ability. It might have hit people hard in a short time, but the amount of thought and care that went into the decision to create this was enormous. We were very appreciative that the wines were well-received.

You must be looked upon as a role model for women in what is typically a masculine industry?

It’s so interesting you should say that because one of my fears in changing my life around was to go into an industry that was not known to be welcoming to women. My grandmother was a Boston Suffragette and my mother accomplished a lot in women’s rights – the glass ceiling was crashing, for me. I had gone to Vassar, which also was a university famous for its women’s achievements. I did come to a crossroads where I asked myself if this was really the right place for me. I’m not a combative person at all, I’m a collaborative person and I’m sure in time, I’ll make my place. Interestingly, in parallel to my decision, a lot of other women were coming into the wine world and it’s been fascinating to see how much has changed in the 10 years that I’ve been selling wine. It’s really encouraging and I think men have enjoyed having women in the wine world. Winemakers are lucky in that they tend to like other winemakers – there is occasional competitiveness – but they’re jovial, happy people who enjoy life. It’s a lovely microcosm.

Who is your own role model?

In the winery and the vineyard, I’ve had the great fortune of working with Zelma Long, who’s a most famous female oenologist. She’s an incredible influence to a whole generation of winemakers who have been the pioneers of the great vineyards of tomorrow. I constantly need the reinforcement and ability to showcase these high-altitude properties because we have everything we need to be one of the great wine regions – our terroir necessitates that.

In the broader existential sense, my role models have always been people who know how to take apart traditional expectations and present them in better ways. One step back, two steps forward. Everything is ripe fruit hanging from the tree around you, to be reinvented to be exciting and different. And that’s where I hope my role will be in the wine world – to bring that energy.

And who, if anyone, has been your most impactful mentor in the journey that you’ve gone through?

My husband is such a clear-headed, forward-thinking person and his values and ability to not get distracted by the noise is a great help to me. I get undue credit for some of the things that happen at this vineyard, as he was really the person who founded it and got it going. His sister and her husband have joined us on the property and have dedicated themselves to helping us and they’re amazing. I couldn’t do it without them.

How important are collaborations to you in your strategy?

It’s so important that I put it on the label! ‘Not mine, not yours, but ours’ – there isn’t a way that we could’ve got to this point without it. We’ve done a project with Pont des Arts (Bridge of Arts), a company started by Thibault Pontallier, son of Paul Pontallier, the iconic winemaker from Chateaux Margaux; and Arthur de Villepin, the son of former French Prime Minister, Dominique de Villepin. They both had fathers who were very big art collectors and have started a business where they match artists and great winemakers, who make special cuvées based on their interpretation of the artist’s work. We made a limited-edition rosé from a painting by Miquel Barceló, where he’s depicted a bullfight, using Grenache from some old vines that had big, gnarly trunks to resonate with the artwork.

What’s next for Chêne Bleu?

We need to figure out where the world is going and what’s going to bring about change in the wine world. Since our first vintage in 2006, I’ve looked at the future of geopolitics, tech, finance, economics; but also, the future of luxury, of gastronomy, of society, and ecology. I wasn’t the only one asking those questions, so I created a think tank session – Fine Minds for Fine Wines. We looked at the luxury world, and at societal and technological factors during roundtables and, off the back of that, we set our own strategy. It also set in motion the creation of a broader agenda, to create a forum for the wine world and there’s now talk of creating an institute for fine wine.

Many niche companies need to do a better job of transitioning from analogue to digital. On the wine side, we’re very excited about the quality of the wines. On the communication front, I’d love to spread the word and we have some big ideas about how to get our message out there.

I knew when I undertook this, it was a big commitment and would be a big challenge, especially from such a remote location. But in the process of doing that, I discovered that I’m not alone in waking up in the morning with big hopes and dreams of doing something that’s really meaningful; not just for now, but for future generations. I guess one of the surprising side effects of being such hardliners in terms of quality has been to enjoy watching Chêne Bleu become a symbol for a way of thinking about things. It has a dimension that goes beyond the product and the place, and really captures the purpose. I seek and welcome collaborations with anybody who shares those values. That’s the beginning of a new chapter in our adventure and one that I think will be just as exciting and challenging as the first 10 years.